Katrin Schwanitz writes about cross-national variation in transition to adulthood.

Background

Since the 1980s, demographic and sociological research on family living arrangements of young adults in Europe has revealed striking and persisting variation in family living arrangements and the transition to adulthood. Despite this, young adults’ living arrangements remain a relatively understudied issue relative to other demographic topics.

What we know about family living arrangements in Europe is based on single-country studies, or comparisons of a small number of mainly Western European countries. Central and Eastern European countries have not yet been systematically included in comparative research on family living arrangements and the transition to adulthood – mainly due to a lack of comparable data. From a family demography perspective, Mandic (2008, p. 616) even referred to this part of Europe as “terra incognita”.

My PhD research deliberately takes a broader view on the transition to adulthood across Western, Central, and Eastern Europe. A cross-national comparative analysis of young adults’ family living arrangements can tell us something about critical interdependencies between young adults themselves and the countries they live in.

In this blog post, I look at transitions to adulthood, and describe two aspects that have not been investigated cross-culturally in detail before. Firstly, I describe the cross-national and cross-temporal variety of young adults’ family living arrangements in eight European countries. Secondly, I take a dynamic-holistic perspective – where multiple dimensions of the life course intersect across time – in order to identify different transitions to adulthood. (My dissertation also looks in more detail at cross-regional differences in intergenerational co-residence (Chap. 3) and cross-national diversity in leaving the parental home (Chap. 5) – lending more support to the differential weight of variables in different contexts.)

Diversity of Family Living Arrangements across Countries

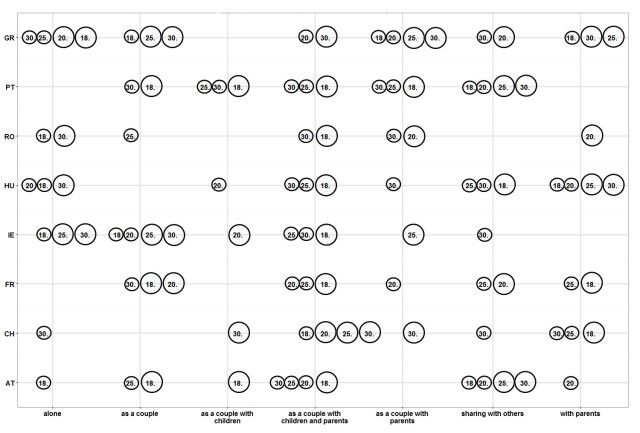

In order to provide a detailed picture of how young adults live across European countries, family living arrangements must be carefully conceptualized to include a variety of extended family and non-family living arrangements. Figure 1 illustrates the over- and underrepresentation of each living arrangement by country and age group with bigger circles indicating greater overrepresentation. For example, we see for the living arrangement alone in Hungary (HU) two small circles for the age groups of 18–19 and 20–24 years and one big circle for the age group 30–34 years. This indicates that living alone is underrepresented in the two younger age groups but overrepresented in the oldest age group among young men in Hungary.

Overall, Figure 1 shows us that, net of demographic controls, (1) non-family arrangements (i.e., living alone or sharing with others) are significantly more common in Western European countries, whereas (2) extended family arrangements (i.e., living with parents, living as a couple with parents and/or extended family, and living as a couple with children and parents and/or extended family) are significantly more common in Southern and Eastern Europe. This pattern is generally compatible with longstanding, systemic variation in family forms and cultures that follows a North – South gradient, such that we may even speak of a North/West – South/East gradient.

Figure 1. Age Differences in Young Men’s Living Arrangements. Conditional associations between age group and living arrangement, by country

Source: IPUMSi, own calculations. Note: AT = Austria; CH = Switzerland; IE = Ireland; FR = France; GR = Greece; HU = Hungary; PT = Portugal; RO = Romania. The figure displays the parameter estimates for the three-way interaction between family living arrangement, country and age group (λ_ijt^LCA). We only considered parameter estimates with an effect size larger than 0.10 and with p<0.05. Big circles represent positive parameter estimates (overrepresentation) and small circles represent negative parameter estimates (underrepresentation).

Diversity in Life Course Trajectories across Europe

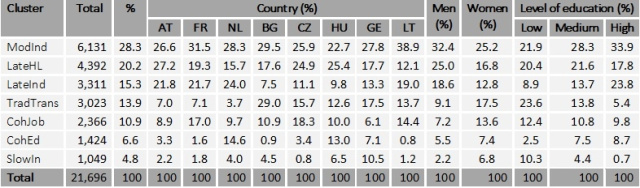

How do life course trajectories differ between educational groups and between men and women? I took into account young adults’ residential, partnership, parental and employment trajectories, and identified seven different types of transitions to adulthood: (1) Modern and Independent ‘ModInd’; (2) Late Home Leavers ‘LateHL’; (3) Late Transitions and Independence ‘LateInd’; (4) Traditional Transitions ‘TradTrans’; (5) Cohabiting with a Job ‘CohJob’; (6) Cohabiting with education ‘CohEd’; and (7) Slow Transitions with Inactivity ‘SlowIn’ (Table 1).

The level of education is an important predictor of life course trajectories for both men and women – generally young adults with higher education are more likely to belong to life course trajectories with late labor market entry and independence, and where cohabitation is included, but marriage and childbearing are postponed. The higher the educational level, the less standard – i.e., following a common age and sequencing pattern – the transition to adulthood. Young adults with low education, experience a faster entry into the labor market, an earlier exit from the parental home, and earlier family formation. Also, there are important gender differences in the life course of young Europeans. Young women are more likely to follow family-oriented trajectories and trajectories linked to inactivity. For example, there is a higher share of women in the groups TradTrans and CohJob, where young adults start working early (before 20) and tend to prioritize family formation over single living. Young European men, however, are much more likely to leave their parents’ home later, to stay longer in education (LateHL and LateInd), and to postpone partnership and family formation (ModInd).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Clusters of Pathways to Adulthood and Cluster Distribution by Country, Sex, and Education

Source: GGS Wave 2 (2006–2013). Own calculations. Note: ModInd = Modern and Independent; LateHL = Late Home Leavers; LateInd = Late Transitions and Independence; TradTrans = Traditional Transitions; CohJob = Cohabiting with a Job; CohEd = Cohabiting with education; SlowIn = Slow Transitions with Inactivity. AT = Austria, FR = France, NL = Netherlands, BG = Bulgaria, CZ = Czech Republic, HU = Hungary, GE = Georgia, LT = Lithuania.

The transition to adulthood varies strongly by country. For example, modern life course pathways such as ‘Modern and Independent’, ‘Late Home Leavers’ and ‘Late Transitions and Independence’ (characterized by a late exit from the parents’ home and being single for a longer period of time and cohabitation) are more common in West European countries. More traditional patterns (‘Traditional Transitions’, ‘Cohabiting with Education’ and ‘Slow Transitions with Inactivity’), however, are more likely to occur in East European countries where young adults follow more classical pathways (they complete their education, start working, marry early, and then have their first child relatively soon). Importantly, the association between education and young adults’ life course trajectories vary by country. For example, educational levels have a positive effect for young East Europeans following a more modern pathway (ModIn), but we find no such effect for young Europeans from Austria, France and the Netherlands. The fact that the trajectories of the European countries globally come together along the lines of the classical welfare regime typology suggests that institutions and policies still leave a clear mark on the different stages of the path towards adulthood.

Family Living Arrangements in Europe: Main Conclusions

My analyses have highlighted that, while young adults’ family living arrangements vary with individual characteristics across European countries, the different individual characteristics (e.g., income, preferences, education) appear to have different weight in different regional and national contexts. A case in point is the differential effect of parental education on leaving home, which is generally in line with anticipated patterns across welfare state regimes (Chap. 5). Also, income has less relevance for determining intergenerational co-residence in more familialistic regions, where family arrangements are more standard (Chap. 3). Even if country-level differences remain prominent, it seems indeed imperative for future research to consider how regional and country contexts channel the impact of individual characteristics. Another lesson from this research is that in examining young adults’ family living arrangements and the transition to adulthood, a spectrum of levels and units must be distinguished and recognized beyond just ‘country’ namely: region, historical generation, family, dyad (partners, parent-child) and the individual.

You may ask why knowledge about young adults’ family living arrangements and the transition to adulthood would be of interest to demographers, policy makers, and the wider public. Unlike other demographic topics – think of childlessness or population ageing, for instance – the link between research on the transition to adulthood and social policy is not self-evident. However, a closer examination of young adults’ family living arrangements and the transition to adulthood in Europe is important demographically, because of the major effects on the “traditional” demographic processes (e.g., births, migrations, and marriages) and the implications for social policy. For example, obstacles to leaving home are likely to lead to postponement of co-residential union formation and subsequent childbearing. Gaining new insights into when and how young adults leave the parental home thus helps us to – at least indirectly – anticipate patterns in other life domains, which then in turn relate to social policy. Cross-national comparisons have, furthermore, demonstrated that variation in family living arrangements and the transition to adulthood cannot be understood without looking beyond the individual. By identifying the critical conditions that promote or hinder the realization of specific family living arrangements, cross-national comparisons can inform policies to advance young adults’ abilities to freely choose when they leave the parental household and with whom they live. Finally, knowledge about young adults’ family living arrangements has potential benefits for housing policy. For example, with whom young adults live after leaving the parental home (alone vs. with a partner) bears implications for the need for new social housing. If access to already existing social housing is difficult, housing policies could counteract a delay in leaving home by facilitating and subsidizing access of young people to rented dwellings.

A basis for implementing various social and housing policies across Europe can only be grounded on demographic knowledge – to provide relevant information to policy-makers and to set the right tone for discussions related to young adults’ family living arrangements and the transition to adulthood.

Author: Katrin Schwanitz is a family demographer with a background in longitudinal and life course research. She currently holds a position as postdoctoral researcher at the Centre of Excellence in Interdisciplinary Lifecourse Studies and the Estonian Institute for Population Studies, Tallinn University. The blog post is based on her PhD project “Family living arrangements in young adulthood: Cross-national comparative analyses”, which was conducted at the Institut National d’Études Démographiques, Paris, France and the Population Research Centre, University of Groningen, Netherlands.

[…] humans are very reserved by nature and nothing about flashy fashion can make its way to their living arrangement regardless of what style statement it makes. So, ensure you keep this tip when buying because […]